Publications

|

Books Meaningful Resistance: Market Reforms and the Roots of Social Protest in Latin America. Cambridge University Press, 2016. Rethinking Comparison: Innovative Methods for Qualitative Political Inquiry (edited with Nicholas Rush Smith). Cambridge University Press 2021. Peer-reviewed articles “Ethnographic Approaches to Contentious Politics: The What, How, and Why” (with Diana Fu). Comparative Political Studies. 54:10 (September 2021) p. 1695-1721. “Targets, Grievances, and Social Movement Trajectories.” Comparative Political Studies. 54: 10 (September 2021), pp. 818-1848. "The Case for Comparative Ethnography." (with Nicholas Rush Smith). Comparative Politics. 51:3 (April 2019) pp. 341-359. “Comparison with an Ethnographic Sensibility” (with Nicholas Rush Smith). PS: Political Science and Politics 50:1 (January 2017), pp. 26-30. “Corn, Markets, and Mobilization in Mexico.” Comparative Politics 48:3 (April 2016), pp. 413-431. “Market Reforms and Water Wars.” World Politics 61:1 (January 2016), pp. 37-73. “Grievances Do Matter in Mobilization.” Theory and Society 43: 5 (September 2014), pp. 513-536. “Coping by Colluding: Political Uncertainty and Promiscuous Power Sharing in Indonesia and Bolivia” (with Dan Slater). Comparative Political Studies 46: 11 (November 2013), pp. 1366-1393. “Informative Regress: Critical Antecedents and Historical Causation” (with Dan Slater). Comparative Political Studies 43:7 (July 2010), pp. 886-917. Other Publications “The Case for Comparative Ethnography” (with Nicholas Rush Smith). Qualitative and Multi-Method Research Newsletter 13:2 (Fall 2015), pp. 13-18. “Informative Regress: Critical Antecedents and Historical Causation” (with Dan Slater). Qualitative Methods 6:1 (Spring 2008), pp. 6-13. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Selected Grants and Awards

2024. Romnes Faculty Fellowship. Awarded by the University of Wisconsin–Madison to recognize excellence in research accomplishments. $60,000 to fund continued research.

2017. Charles Tilly Distinguished Contribution to Scholarship Book Award for Meaningful Resistance: Market Reforms and the Roots of Social Protest in Latin America. Awarded by by the Collective Behavior and Social Movements Section of the American Sociological Association.

2017. American Political Science Association, Science, Technology, and Environmental Politics Best Paper Award for "Market Reforms and Water Wars."

2017. National Science Foundation Grant. “Rethinking Comparison in the Social Sciences.” Award #MSN203325. $49,944 to fund a workshop and an edited volume on qualitative comparative methods.

2016. Sage Paper Award for the best paper applying or developing qualitative methods presented at the American Political Science Association. Awarded to "Comparison and Ethnography: What Each Can Learn From the Other" (with Nicholas Rush Smith).

2013. Latin American Studies Association-Oxfam America Martin Diskin Award for best dissertation involving a combination of scholarship and activism (co-awarded).

2010. Mellon Foundation Dissertation-Year Fellowship.

2008. Sage Paper Award for the best paper applying or developing qualitative methods presented at the American Political Science Association. Awarded to "Informative Regress: Critical Antecedents and Historical Causation” (with Dan Slater).

2008. Fulbright Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research Award.

2017. Charles Tilly Distinguished Contribution to Scholarship Book Award for Meaningful Resistance: Market Reforms and the Roots of Social Protest in Latin America. Awarded by by the Collective Behavior and Social Movements Section of the American Sociological Association.

2017. American Political Science Association, Science, Technology, and Environmental Politics Best Paper Award for "Market Reforms and Water Wars."

2017. National Science Foundation Grant. “Rethinking Comparison in the Social Sciences.” Award #MSN203325. $49,944 to fund a workshop and an edited volume on qualitative comparative methods.

2016. Sage Paper Award for the best paper applying or developing qualitative methods presented at the American Political Science Association. Awarded to "Comparison and Ethnography: What Each Can Learn From the Other" (with Nicholas Rush Smith).

2013. Latin American Studies Association-Oxfam America Martin Diskin Award for best dissertation involving a combination of scholarship and activism (co-awarded).

2010. Mellon Foundation Dissertation-Year Fellowship.

2008. Sage Paper Award for the best paper applying or developing qualitative methods presented at the American Political Science Association. Awarded to "Informative Regress: Critical Antecedents and Historical Causation” (with Dan Slater).

2008. Fulbright Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research Award.

Statement of Research Interests

My research is motivated by an interest in contentious politics and qualitative methods. My regional area of expertise is Latin America. I am currently actively pursuing three projects. First, I am exploring state responses to social mobilization by asking questions about why and how states respond the ways they do when confronted by contentious actors. Second, I am interested in the intersection of extractive economies and ideals of plurinational governance. I am asking questions about how states reconcile redistributive goals, commitments to indigenous autonomy, and legacies of development rooted in natural resource extraction. Third, I am building on a recently published book on qualitative methods to launch a new project that explores how we think about generalizability in the social sciences. I expand on each below.

State responses to social mobilization.

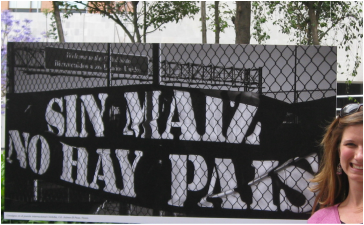

This research agenda builds directly on my book, Meaningful Resistance: Market Reforms and the Roots of Social Protest in Latin America (Cambridge University Press 2016, recognized with the 2017 Charles Distinguished Contribution to Scholarship Book Award from the American Sociological Association). The book explores the origins and dynamics of resistance to markets through a careful examination of two cases in which social movements emerged to voice and channel opposition to market reforms. Protests against water privatization in Cochabamba, Bolivia and rising corn prices in Mexico City, Mexico offer a lens through which to analyze and understand the mechanisms through which perceived, market-driven threats to material livelihood can prompt resistance. Through exploring connections between marketization, local practices and understandings, and political protest, the book shows how the material and the ideational are inextricably linked in resistance to subsistence threats. When people perceive that markets have put subsistence at risk, material and symbolic worlds are both at stake; citizens take to the streets not only to defend their pocketbooks, but also their conceptions of community.

I am continuing to pursue these questions, but now through the lens of the state. While the book and related articles ask questions focusing on social movement actors, the current project looks to the targets of a social movement’s claims and explores questions about how and why they respond to social mobilizations in the ways they do. If we can better understand why states perceive social movements as threatening when they do we fill a critical gap in our understanding of social movement trajectories; social movements can grow and fade as a direct result of state actions. To explore these questions, I apply the insights generated from the book—specifically that the meanings with which grievances are imbued shape social movement dynamics—and show how perceptions of grievances shape a target’s response to social mobilization. I contend that a target’s understanding of a social movement’s claims shapes its response, which, in turn, shapes the evolution of the social movement. I make the argument through a careful examination of the Bolivian and Mexican cases that were at the core of the book. In each case, differences in how public authorities understood the movements’ claims helps to explain why they reacted in starkly different ways to the emerging movements. Where officials appreciated the symbolic value of the goods at stake they acted quickly to curtail resistance. Where officials failed to grasp those meanings, they dismissed the potential for widespread mobilization, and inadvertently accelerated movement growth. An article based on the book project was published in Comparative Political Studies in 2021. I expect to submit the book manuscript to Cambridge University Press in June 2022.

Extractive economies and plurinational governance

In this project I explore the legacies of an extractive state on the one hand, and ideals of plurinational governance and politics of redistribution on the other. I investigate the ways in which the development and exploitation of natural resources by state actors affect possibilities for and conceptions of nation and national belonging. How does the articulation of development priorities that require resource extraction intersect with local conceptions of resource use? How do state commitments to plurinationalism surface throughout these processes? What do these tensions reveal about the meanings that concepts like “development” and “progress” take on in different contexts?

I take up these questions through the lens of conflict over extraction in the Isoboro Secure National Park and Indigenous Territory (TIPNIS) in eastern Bolivia in 2011. When Bolivian President Evo Morales proposed the construction of a road through the TIPNIS Park, 80% of which had been set aside and protected as indigenous territory, social mobilization and direct conflict with the state ensued. Morales had inherited a legacy of development that would be hard to shed—Bolivia had long relied on its natural resources for economic growth. Morales’ ambitious plans for social development programs relied on natural gas extraction. Commitments to indigenous autonomy appeared to be odds with these national development goals. The TIPNIS events offer the perfect lens through which to explore the intersection of multiple and sometimes overlapping national commitments and claims, extractive development projects, and redistributive goals. The conflict shows how plurinational ideals might be difficult to reconcile with the implementation of a resource nationalist development agenda. In the TIPNIS case, the state appears to have run roughshod over local priorities and the cultural logics of indigenous autonomy in the name of national development goals.

This project advances contemporary scholarship by bridging debates on natural resource extraction, nationalism and indigeneity, and the rise of the Latin American left. The project also has important empirical implications for our understandings of how national commitments and social welfare goals shape natural resource policies and conflicts. The project is still in the initial data gathering and theory-building stage. Articles are in progress and I intend to produce a book-length manuscript.

Qualitative Methods in the Social Sciences

The methodological challenges posed by my research have generated an interest in and commitment to the importance of qualitative methods. In collaboration with my colleague, Nicholas Rush Smith, I have just completed Rethinking Comparison: Innovative Methods for Qualitative Political Inquiry (Cambridge University Press, 2021). Funded with a grant from the National Science Foundation, the book builds on my previous methodological work with Dan Slater and Nicholas Smith (published in Comparative Political Studies, Comparative Politics, and PS: Political Science and Politics) but takes a wider approach to push the discipline to engage with broad questions of comparison.

Rethinking Comparison brings together leading political science scholars to explore two of the most fundamental questions in the study of politics: (1) why do we compare what we compare and (2) how do the methodological assumptions we make about why and how we compare shape the knowledge we produce? Qualitative comparative methods—and specifically controlled qualitative comparisons–have been central to some of the most influential works of social science. Yet even as controlled comparisons have produced lasting insights and continue to dominate research designs, they are not the only form of comparison that scholars utilize. There is little methodological guidance, however, for how to design or execute comparisons that do not rely on control as a central element. The consequences for knowledge are severe. When we limit the kinds of comparisons that we make, we necessarily constrain the kinds of questions that we ask, and therefore limit the knowledge we produce. Rethinking Comparison seeks to systematize how to do alternative forms of comparison. By systematically thinking through how we engage in qualitative comparisons, elaborating why such comparisons should be compelling, and providing scholars with a vocabulary to describe their approach, the book provides a foundation for expanding the possibilities for inquiry in political science. The book not only gives scholars additional techniques to advance what know about politics, but also make those techniques more accessible. It serves as a resource for future students and scholars of politics who are looking to engage in forms of comparison that go beyond controlled approaches, providing an important complement to works on controlled comparison that currently dominate syllabi.

Building on the success of, and demand for, the ideas developed in Rethinking Comparison Smith and I have just launched a new project on generalizability. Throughout the course of our conversations on comparisons it was clear that a crucial, parallel question demanded attention: How does the knowledge we generate generalize to other contexts? The answer to this question has implications for how we design our research projects, how we draw on insights generated by other scholars, and the interventions we propose to solve real-world policy problems. We contend that current approaches to generalization—including what we understand generalization to be and the kinds of findings we need to have in order to talk about generalization—limit the kinds of questions we ask and hence the kind of knowledge we produce. Our objectives with this new project two-fold: (1) to offer political scientists new tools for thinking through how they conceive of the logics behind generalization and (2) to offer political scientists new goals for their research that extend beyond generalization altogether. To achieve this goal, we seek to both build new logics of generalization and to clearly articulate logics that some scholars are already using but remain underdeveloped. As we did with Rethinking Comparison, we aim to bring together leading scholars from across the subfields of political science to think together about how they understand generalizability in the social sciences. To the degree that dominant approaches to generalization seek a unified approach to explanatory research we propose to do the opposite: to equip scholars with heterogenous outcomes for their research to seek. In doing so, we seek to pluralize explanatory goals. We have already begun to organize an initial workshop for the project to be held October 2023 and are currently preparing a grant proposal for NSF funding. Smith and I have also written two working papers developing our own thoughts on generalizability.

State responses to social mobilization.

This research agenda builds directly on my book, Meaningful Resistance: Market Reforms and the Roots of Social Protest in Latin America (Cambridge University Press 2016, recognized with the 2017 Charles Distinguished Contribution to Scholarship Book Award from the American Sociological Association). The book explores the origins and dynamics of resistance to markets through a careful examination of two cases in which social movements emerged to voice and channel opposition to market reforms. Protests against water privatization in Cochabamba, Bolivia and rising corn prices in Mexico City, Mexico offer a lens through which to analyze and understand the mechanisms through which perceived, market-driven threats to material livelihood can prompt resistance. Through exploring connections between marketization, local practices and understandings, and political protest, the book shows how the material and the ideational are inextricably linked in resistance to subsistence threats. When people perceive that markets have put subsistence at risk, material and symbolic worlds are both at stake; citizens take to the streets not only to defend their pocketbooks, but also their conceptions of community.

I am continuing to pursue these questions, but now through the lens of the state. While the book and related articles ask questions focusing on social movement actors, the current project looks to the targets of a social movement’s claims and explores questions about how and why they respond to social mobilizations in the ways they do. If we can better understand why states perceive social movements as threatening when they do we fill a critical gap in our understanding of social movement trajectories; social movements can grow and fade as a direct result of state actions. To explore these questions, I apply the insights generated from the book—specifically that the meanings with which grievances are imbued shape social movement dynamics—and show how perceptions of grievances shape a target’s response to social mobilization. I contend that a target’s understanding of a social movement’s claims shapes its response, which, in turn, shapes the evolution of the social movement. I make the argument through a careful examination of the Bolivian and Mexican cases that were at the core of the book. In each case, differences in how public authorities understood the movements’ claims helps to explain why they reacted in starkly different ways to the emerging movements. Where officials appreciated the symbolic value of the goods at stake they acted quickly to curtail resistance. Where officials failed to grasp those meanings, they dismissed the potential for widespread mobilization, and inadvertently accelerated movement growth. An article based on the book project was published in Comparative Political Studies in 2021. I expect to submit the book manuscript to Cambridge University Press in June 2022.

Extractive economies and plurinational governance

In this project I explore the legacies of an extractive state on the one hand, and ideals of plurinational governance and politics of redistribution on the other. I investigate the ways in which the development and exploitation of natural resources by state actors affect possibilities for and conceptions of nation and national belonging. How does the articulation of development priorities that require resource extraction intersect with local conceptions of resource use? How do state commitments to plurinationalism surface throughout these processes? What do these tensions reveal about the meanings that concepts like “development” and “progress” take on in different contexts?

I take up these questions through the lens of conflict over extraction in the Isoboro Secure National Park and Indigenous Territory (TIPNIS) in eastern Bolivia in 2011. When Bolivian President Evo Morales proposed the construction of a road through the TIPNIS Park, 80% of which had been set aside and protected as indigenous territory, social mobilization and direct conflict with the state ensued. Morales had inherited a legacy of development that would be hard to shed—Bolivia had long relied on its natural resources for economic growth. Morales’ ambitious plans for social development programs relied on natural gas extraction. Commitments to indigenous autonomy appeared to be odds with these national development goals. The TIPNIS events offer the perfect lens through which to explore the intersection of multiple and sometimes overlapping national commitments and claims, extractive development projects, and redistributive goals. The conflict shows how plurinational ideals might be difficult to reconcile with the implementation of a resource nationalist development agenda. In the TIPNIS case, the state appears to have run roughshod over local priorities and the cultural logics of indigenous autonomy in the name of national development goals.

This project advances contemporary scholarship by bridging debates on natural resource extraction, nationalism and indigeneity, and the rise of the Latin American left. The project also has important empirical implications for our understandings of how national commitments and social welfare goals shape natural resource policies and conflicts. The project is still in the initial data gathering and theory-building stage. Articles are in progress and I intend to produce a book-length manuscript.

Qualitative Methods in the Social Sciences

The methodological challenges posed by my research have generated an interest in and commitment to the importance of qualitative methods. In collaboration with my colleague, Nicholas Rush Smith, I have just completed Rethinking Comparison: Innovative Methods for Qualitative Political Inquiry (Cambridge University Press, 2021). Funded with a grant from the National Science Foundation, the book builds on my previous methodological work with Dan Slater and Nicholas Smith (published in Comparative Political Studies, Comparative Politics, and PS: Political Science and Politics) but takes a wider approach to push the discipline to engage with broad questions of comparison.

Rethinking Comparison brings together leading political science scholars to explore two of the most fundamental questions in the study of politics: (1) why do we compare what we compare and (2) how do the methodological assumptions we make about why and how we compare shape the knowledge we produce? Qualitative comparative methods—and specifically controlled qualitative comparisons–have been central to some of the most influential works of social science. Yet even as controlled comparisons have produced lasting insights and continue to dominate research designs, they are not the only form of comparison that scholars utilize. There is little methodological guidance, however, for how to design or execute comparisons that do not rely on control as a central element. The consequences for knowledge are severe. When we limit the kinds of comparisons that we make, we necessarily constrain the kinds of questions that we ask, and therefore limit the knowledge we produce. Rethinking Comparison seeks to systematize how to do alternative forms of comparison. By systematically thinking through how we engage in qualitative comparisons, elaborating why such comparisons should be compelling, and providing scholars with a vocabulary to describe their approach, the book provides a foundation for expanding the possibilities for inquiry in political science. The book not only gives scholars additional techniques to advance what know about politics, but also make those techniques more accessible. It serves as a resource for future students and scholars of politics who are looking to engage in forms of comparison that go beyond controlled approaches, providing an important complement to works on controlled comparison that currently dominate syllabi.

Building on the success of, and demand for, the ideas developed in Rethinking Comparison Smith and I have just launched a new project on generalizability. Throughout the course of our conversations on comparisons it was clear that a crucial, parallel question demanded attention: How does the knowledge we generate generalize to other contexts? The answer to this question has implications for how we design our research projects, how we draw on insights generated by other scholars, and the interventions we propose to solve real-world policy problems. We contend that current approaches to generalization—including what we understand generalization to be and the kinds of findings we need to have in order to talk about generalization—limit the kinds of questions we ask and hence the kind of knowledge we produce. Our objectives with this new project two-fold: (1) to offer political scientists new tools for thinking through how they conceive of the logics behind generalization and (2) to offer political scientists new goals for their research that extend beyond generalization altogether. To achieve this goal, we seek to both build new logics of generalization and to clearly articulate logics that some scholars are already using but remain underdeveloped. As we did with Rethinking Comparison, we aim to bring together leading scholars from across the subfields of political science to think together about how they understand generalizability in the social sciences. To the degree that dominant approaches to generalization seek a unified approach to explanatory research we propose to do the opposite: to equip scholars with heterogenous outcomes for their research to seek. In doing so, we seek to pluralize explanatory goals. We have already begun to organize an initial workshop for the project to be held October 2023 and are currently preparing a grant proposal for NSF funding. Smith and I have also written two working papers developing our own thoughts on generalizability.

Proudly powered by Weebly